Why you should also protect the integrity of the native libraries

Introduction

Nowadays, the developers of mobile applications handling sensitive information are usually aware of the security risks. Open-source and commercial solutions are involved during the build process, providing obfuscation and protections against techniques such as tampering, dynamic instrumentation, debugging, rooting, emulation, etc. These protection techniques have significantly evolved in the last years. Thus, bypassing these mechanisms usually requires advanced reverse engineering skills.

However, there are still security holes that should not be overlooked, as they become low-hanging fruit that can be aimed by not necessarily highly skilled attackers.

An example of how what could be a banking application could be compromised is discussed in this article.

This article is written with the purpose of raising awareness about the importance of taking care of the small details when developing products. A huge defensive system might become useless if we leave an open window somewhere.

Proof of Concept (PoC)

The target application: an impregnable bastion

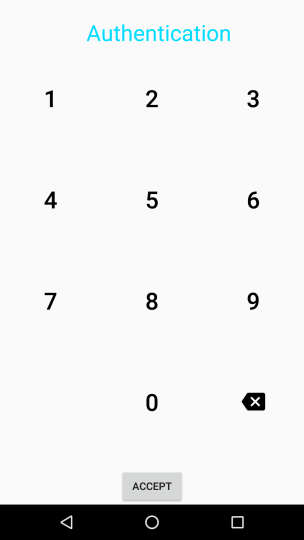

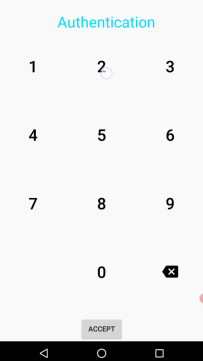

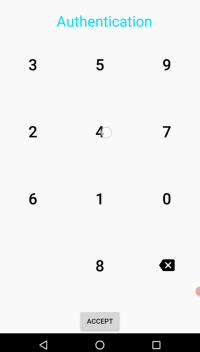

For this demonstration, the target will be an application which requires entering a PIN code to authenticate a user.

The activity than contains the PIN pad is protected against screen captures through the flag FLAG_SECURE:

window.setFlags(WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE,

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE);

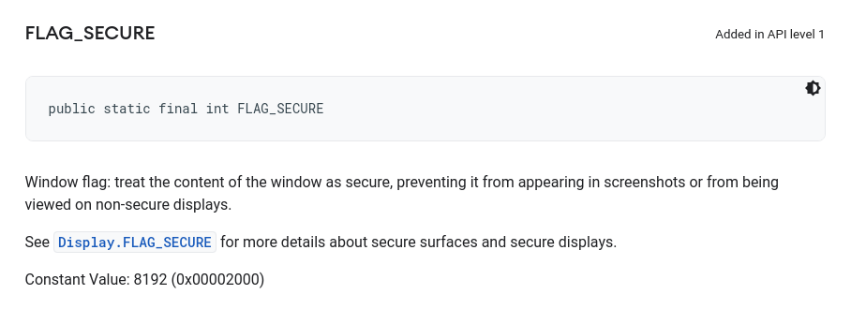

The explanation of the flag FLAG_SECURE from the

Android development site

is shown below:

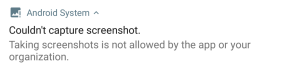

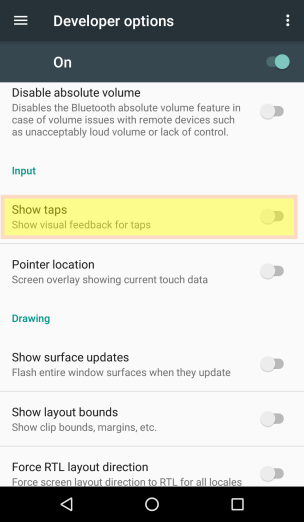

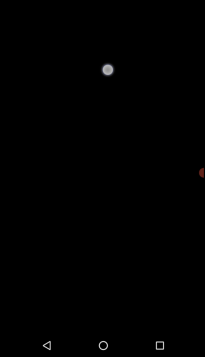

Hence, when this flag is set, capturing the screen is not allowed by the system. For instance, if we try to record the screen it will be shown in black; and if we try to take a screenshot through a button combination, it will not be allowed and a message like the one in the picture below will be shown:

Furthermore, the application does not allow to proceed if the developer options are enabled (adb).

Let us suppose that this application is protected with state-of-the-art techniques against rooting, hooking, debugging, tampering, etc.

Thus, any attempt to hook or tamper with the APK would eventually trigger a security check, preventing the application from running in normal conditions.

Let us also accept that the application is strongly obfuscated, and trying to understand how the security checks work would entail an arduous process of reverse engineering, which requires high skills.

An open window through the fortress

However, all this defensive effort described above might be in vain, as there is a small hole that leads inside of the fortress: the application has a native library whose integrity is not totally protected: libvuln.so.

Loading a malicious native library

The fact that libvuln.so can be modified without being detected, means that we could potentially alter the behaviour of the application. Moreover, the library libvuln.so is loaded before the PIN pad is used. Hence, any modification we might induce, would be effective at the moment when the PIN pad is being used.

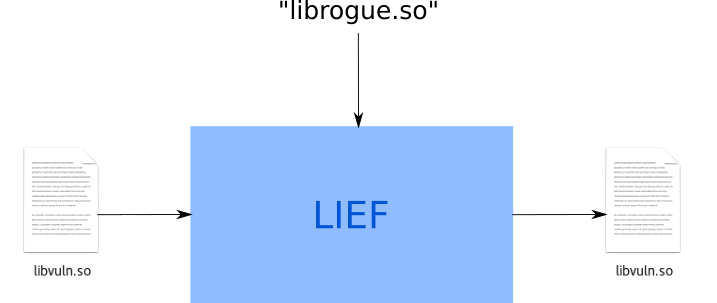

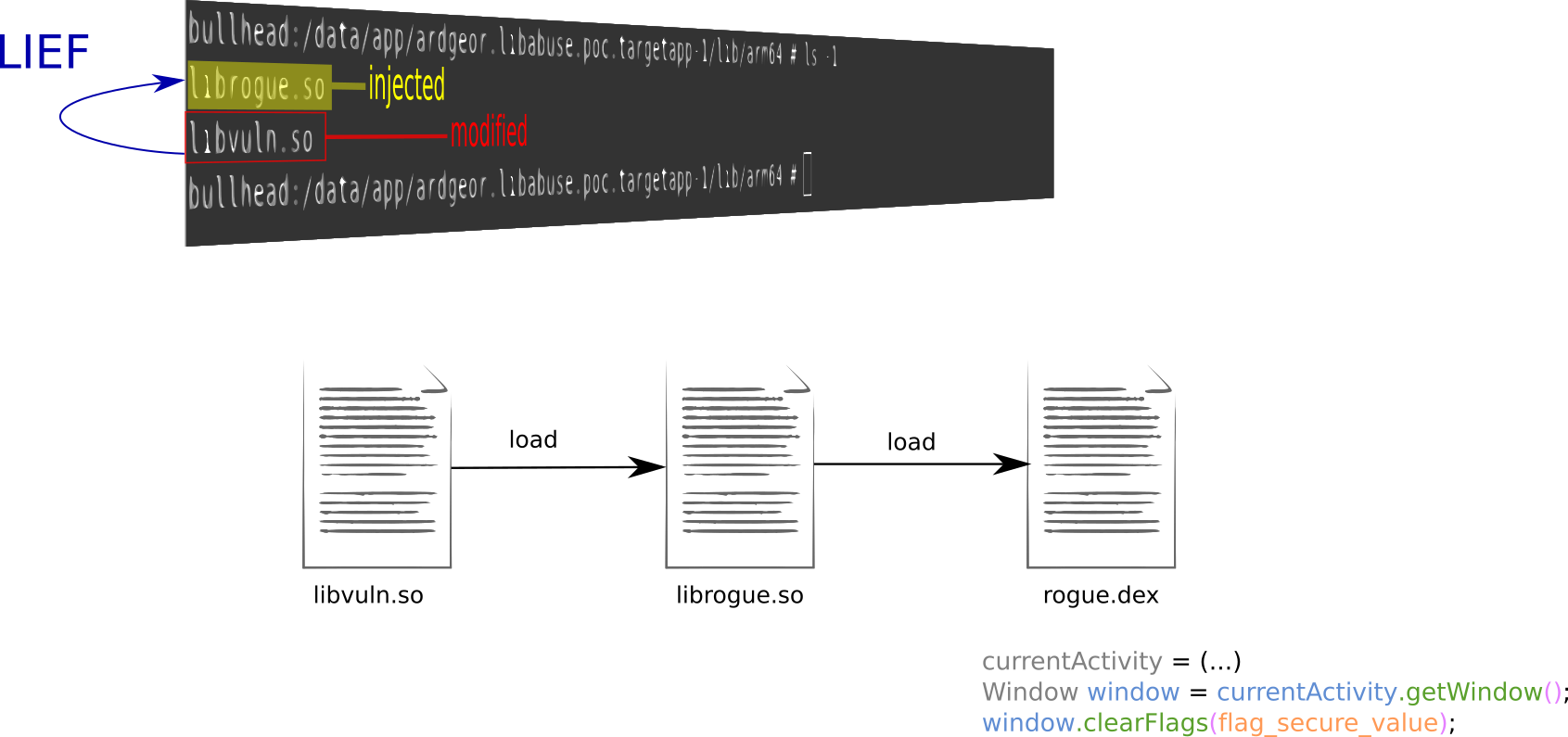

Where to begin? Let us imagine that we have a rogue library, called librogue.so, which contains some malicious functions that we would like to be executed by the target application. Would it be possible? Well, the first problem to solve is that we need this library to be loaded in memory. In order to achieve this, the library libvuln.so could be modified to declare an additional library as a dependency and, hence, make it to be loaded. This can be done with a tool called LIEF, created by the security engineer Romain Thomas.

As depicted below, LIEF takes as input the library to modify, and the name of the library to add as a dependency. The binary produced as a result, will include the name librogue.so as a needed library.

The code to produce this is shown below:

import lief

# (...)

libnative = lief.parse("{}/{}".format(so_input_path, so_input))

libnative.add_library(so_inject) # Injection!

libnative.write("{}/{}".format(so_output_path, so_output))

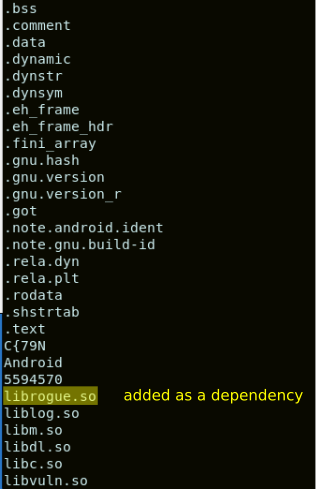

By inspecting the strings of the binary produced, we can confirm that librogue.so had been added to the list of libraries to load:

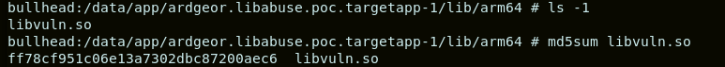

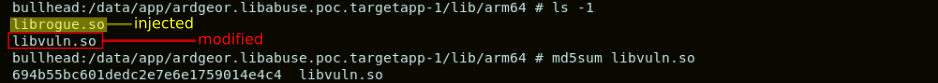

In Android, the libraries embedded in an APK are placed within a directory dedicated for the specific application in the path /data/app. For our case, libvuln.so is placed in /data/app/ardgeor.libabuse.poc.targetapp-1/lib/arm64. For our attack, we would simply replace libvuln.so by the “liefed” version. We would also copy librogue.so in the same directory.

At this point, there are two aspects that need to be clarified:

- Of course, we need to be

rootin order to write in/data/app. However, this does not necessarily entail to bypass the root protection, as this action can be carried out when the application is not running. Thus, it would be enough for an attacker to just temporarily elevate privileges. - Actually, the native libraries are placed in the directory for the application in

/data/appas long as the flagandroid:extractNativeLibsis not set tofalsein the Android manifest. However, if we place the modified version oflibvuln.soin this directory, this will be the binary loaded in memory, as that’s the preferred location.

Once the libraries have been placed in /data/app/ardgeor.libabuse.poc.targetapp-1/lib/arm64, we can launch the application.

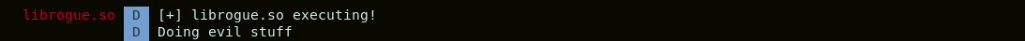

A message in the log reveals that the library librogue.so is executing. No disruptive action is observed. At this point, we can inject our own code in the application and get it executed.

Loading a malicious DEX file

So, we are already able to execute the code from our own native library. What would we like to do at this point?

Thinking as an attacker about a real scenario, it would be great to disable the flag FLAG_SECURE on the PIN activity and add functionality to take screenshots or record the screen, as well as support to send information to a server controlled by the attacker. As we plan to make calls at the Java layer, it would be more convenient to write Java code, generate a DEX file and load it from librogue.so.

The article Three ways for dynamic code loading in Android may serve as inspiration for loading the DEX.

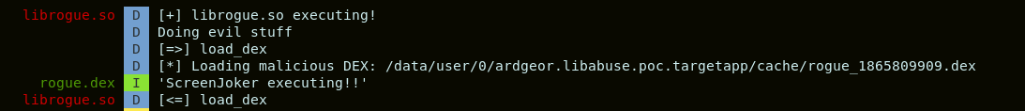

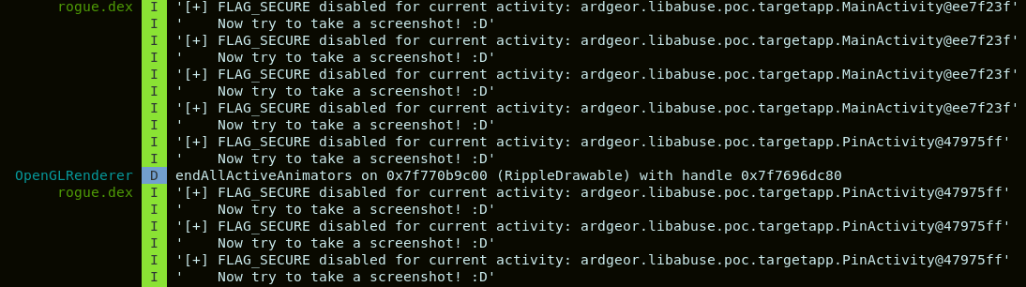

Thus, Java reflection calls were included in librogue.so to use, through the JNI, the class DexClassLoader for loading our DEX rogue.dex. This is shown in the log snippet below:

Enabling screen captures

Good! Now we can inject code both in the native layer and in the Java layer!

Our goal was to disable FLAG_SECURE on the PIN activity.

A simple approach could be to iteratively recover the current activity and disable the flag.

This can be done through reflection calls to specific hidden Android API.

The result can be observed in the log snippet below:

And now we can capture the screen :)

We could summarize this first part in three steps, as shown in the picture below:

- Modify

libvuln.soto indicate thatlibrogue.soneeds to be loaded. - From

librogue.so, loadrogue.dex. - From

rogue.dex, recover the current activity and clear the flagFLAG_SECUREfrom the corresponding window object.

Capturing the PIN

We have seen how it was possible to disable the flag FLAG_SECURE and take screenshots or record the screen.

At this point there are different possibilities, let us go across them and analyze each particular case

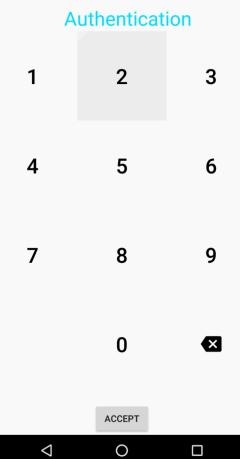

The PIN pad provides a visual feedback when a button is pressed

The easiest case for the attacker would be when a visual feedback is produced when pressing a button of the PIN pad.

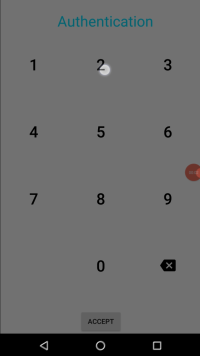

For instance, from the screen shown in the figure below, we can know that the button 2 was pressed, as a shadow appeared on the button.

The PIN pad does not provide a visual feedback when a button is pressed

In the case that no visual effect is produced, such as a shadow or a color change, just being able to observe the screen would not be enough for an attacker to obtain the PIN. An additional capability will be required, related to where the user touched on the screen.

There exists a feature that satisfies this need: the show_touches option, or “show taps”. This can be enabled through the developer options menu:

This apparently solved the problem, except that we had said that the application did not allow the developer options to be enabled…

Enabling the show_touches feature without the developer options

But we had also mentioned that this attack needs the ability to temporarily become root. A root privilege allows to activate the

show_touches setting. However, a shell session independent from ADB is needed.

Let us think again of a real scenario, let’s imagine an attacker that has a remote shell session on the phone through e.g. using the SSH protocol.

The attacker must become root, and the privilege obtained must allow to edit the settings.

If this is achieved, the following command will activate the show_touches option:

\# content insert --uri content://settings/system --bind name:s:show_touches --bind value:i:1

or also:

\# settings put system show_touches 1

A couple of comments about this:

- If the phone reboots, the change is persistent, meaning that the

show_touchesoption will still be active. - If the developer options are enabled, and then disabled,

show_touchesoption will be disabled.

Well, at this point nothing prevents us from capturing the PIN, as shown in the picture below, where a tap appears on the digit 2:

Further discussion

There are more possibilities that could make the attack unfeasible or even easier. For instance, if the position of the buttons is always the same, we don’t really need to * see * the PIN pad, it is enough to see the taps, and then derive the button that was pressed.

Let us see an example. The screen shown below has been captured. As we can see, the flag FLAG_SECURE has not be disabled, but the

show_touches option has been enabled.

If the position of the buttons is static, we can just superimpose a template of the PIN pad on the screen capture, and we obtain the button that was pressed. Or we can directly infer it from the screen capture :)

A more complicated case would be when there is no visual feedback and also the position of the buttons is not predictable.

In this case, we would again need both disabling the flag FLAG_SECURE, in order to see where each button is placed;

and also enable the show_touches option, to obtain visual feedback. An example is shown below:

Finally, if the application checks the show_touches option and refuses to execute normally if it is enabled; and there is no visual feedback on the PIN pad; then, in this case, retrieving the PIN from the screen is, a priori, not possible.

The relevant cases are summarized in the table below:

FLAG_SECURE enabled |

PIN pad buttons at a fixed position | Visual feedback | show_touches detected |

Attack path | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Disable FLAG_SECURE |

Activate show_touches |

||||

| No | X | Yes | No | Not needed | Not needed |

| Yes | X | Yes | No | Yes | Not needed |

| Yes | Yes | X | No | Not needed | Yes |

| Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Yes | X | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Yes | X | No | Yes | Attack not possible |

Summing up

-

The attack paths presented here take advantage from neglected security holes. Namely, absence of integrity checks on the shared objects (*.so), and absence of a explicit check on the

show_touchesoption to be disabled (just a check on the developer options is not enough!). -

The attack requires a shell session as root. Actions will be carried out when the target application is not in use, so no need to worry about security checks (depending on how root has been obtained).

- Depending on the exact case (see the different cases discussed above), different additional requirements would be needed for the attack to be applicable:

- If disabling the

FLAG_SECUREflag is required, an unprotected shared object (being loaded before the PIN pad is used) is needed. - If the

show_touchesoption is needed, the attack privilege must allow to edit the system settings. Moreover, a shell session not related to ADB is needed.

- If disabling the

-

The attack can apply to any application, without customization, as long as the required conditions are fulfilled.

- No reverse engineering is required.

What else?

Note that if we are able to inject code, this opens the door to new attacks :)

Conclusion

- Keep thinking about security, don’t take it for granted.

- Pay attention to the small details. Is there an easy way in somewhere?

- Keep this picture in sight: