When Frida plays in the blue team

Pincha aquí para ver el artículo en español

Introduction

We are used to see Frida as a valuable allied when we are on the attacker’s side. But Frida also happens to be a powerful partner when it comes to defending. This article is about stack buffer overflow, a problem with a lot of history which is not past yet. Attack and defense methods have been competing for over 40 years, becoming more and more sophisticated: canaries, data execution prevention (DEP), return-oriented programming (ROP), address space layout randomization (ASLR), etc.

Now let’s see one of the methods in which dynamic binary instrumentation (DBI) can help protect a vulnerable program.

Stack buffer overflow

The stack buffer overflow problem appears whenever bytes are copied into a buffer with a limited size without having control on how many bytes are actually copied.

In the snippet below, the function main receives data from the command line and passes it to the function processData, where the data is copied into the local variable

buffer. This variable corresponds to an array of 64 characters. Since buffer is a local variable, it lives in the stack.

void processData(char *data) {

char buffer[64];

strcpy(buffer, data); // <---------------- BoF!

printf("Data processed: %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

// (...)

processData(input);

// (...)

}

Let us take a closer look at what happens when a malicious input is passed.

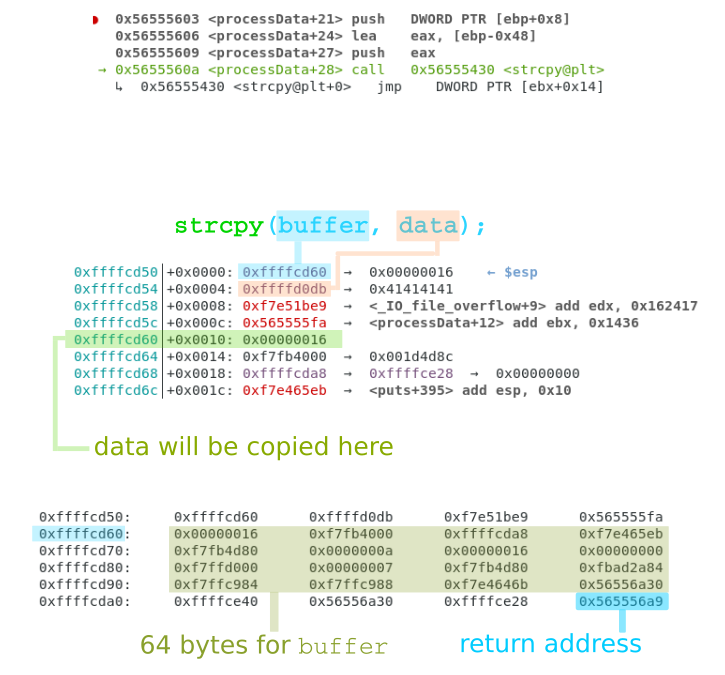

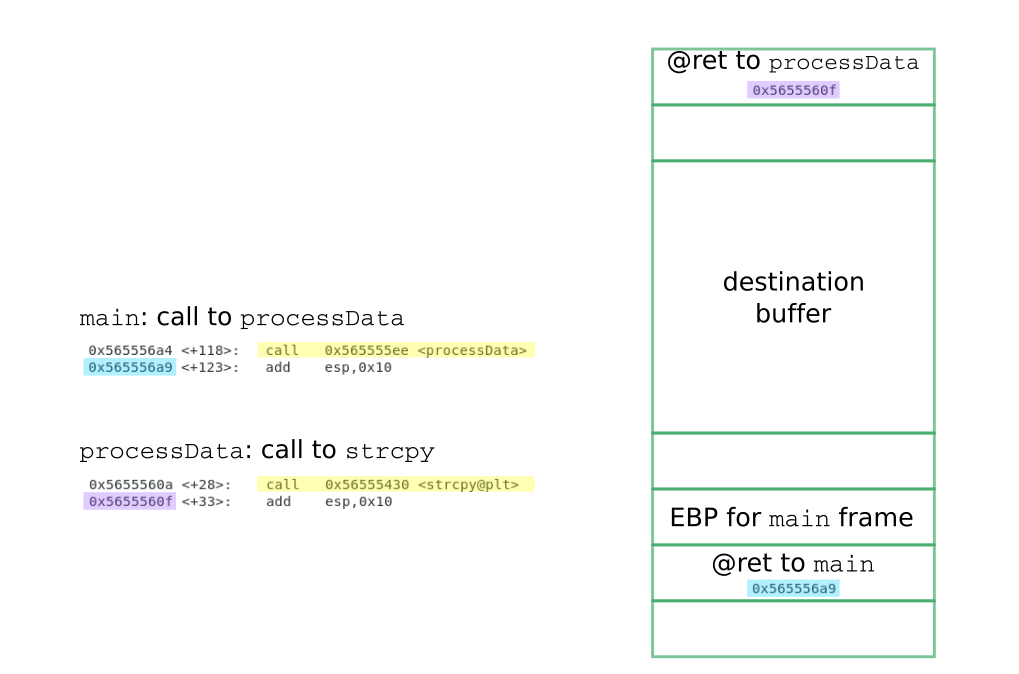

The image below corresponds to the moment right before the data is copied into the array buffer, through the function strcpy.

This function takes its arguments from the stack: the destination address is on the top (0xffffcd60), and the source address is right after (0xffffd0db).

At the bottom of the picture, we can see the 64 bytes allocated for buffer, starting at 0xffffcd60,

and a little further down, there is the address to return from processData to main: 0x565556a9.

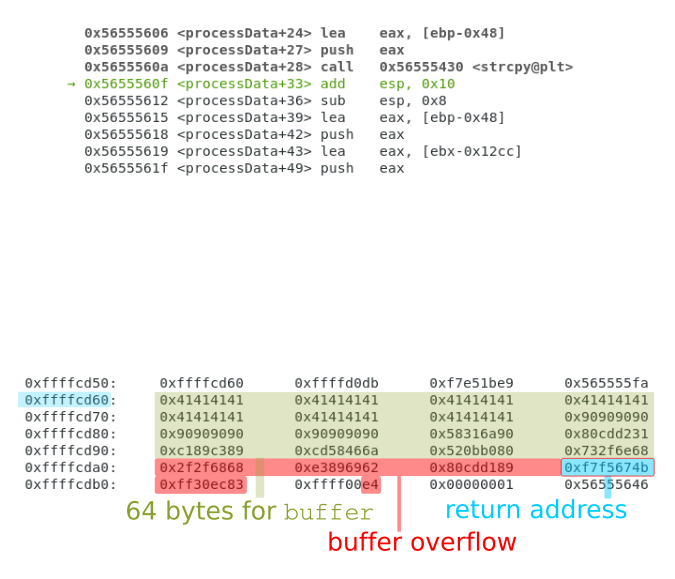

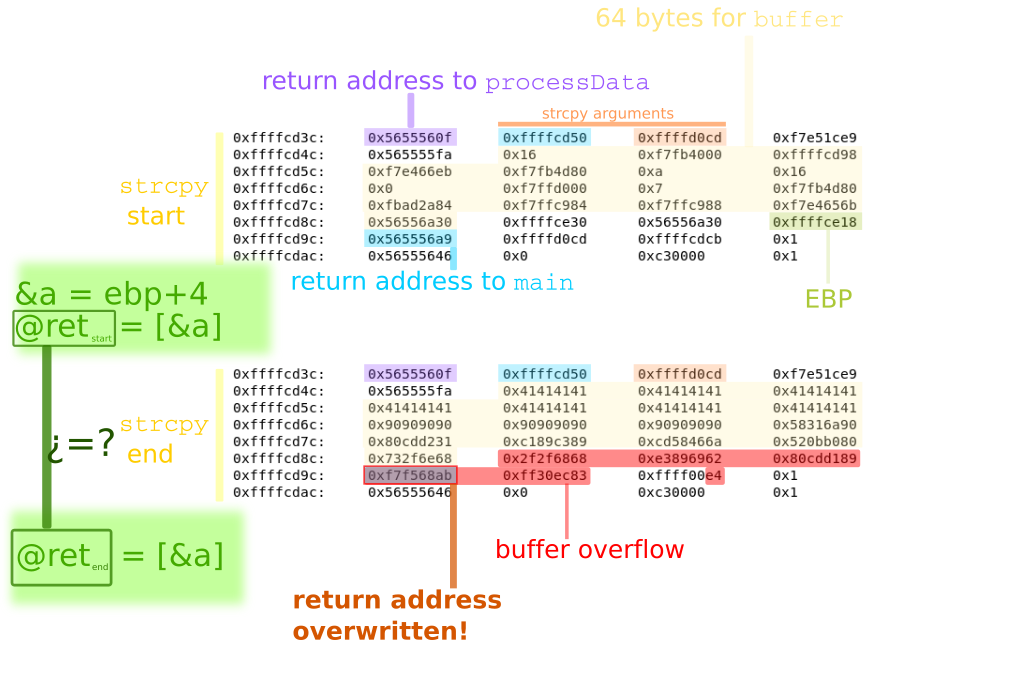

The following image corresponds to the moment when the execution has just returned from strcpy to main.

As it can be observed, data has been copied beyond the 64 bytes that had been assigned, the buffer has been overflowed.

As a result, the address to return from processData to main has changed into 0xf7f5674b, which has been placed there by

the attacker.

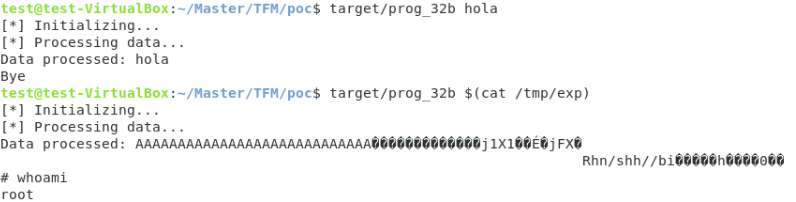

At this point, the execution flow has been redirected, which might entail arbitrary code execution. In the figure below, a shell with root privilege is shown, it was obtained as a result of the exploitation.

Let us now digress a little to explain the concept of dynamic instrumentation, before focusing on how it can help to thwart an exploit as the one we have just seen.

Dynamic binary instrumentation

Dynamic binary instrumentation can be defined as the process of modifying the instructions of a binary program while it executes.

Frida

One of the most popular tools for DBI over the past few years is Frida. It is used by developers, reverse-engineering professionals and security researchers. Frida is powerful, flexible and easy to use. We can work through scripts, it is multi-platform, free software and widely tested. It is no coincidence that a large number of projects and tools have been developed on top of Frida, as it provides an excellent base.

The Interceptor

The Frida Interceptor allows, among other things, to set hooks

on functions and implement callbacks where we can specify actions to be carried out before and after the “hooked” function is executed.

The actions to perform before are defined in the onEnter callback, and the actions to perform after are defined in the onLeave callback.

The Javascript code for using the Interceptor would have a structure as follows, where the target can be a function name or address:

Interceptor.attach(target, {

onEnter(args) {

// actions to be carried out before executing the target function

// (...)

},

onLeave (retval) {

// actions to be carried out after the execution of the target function

// (...)

}

});

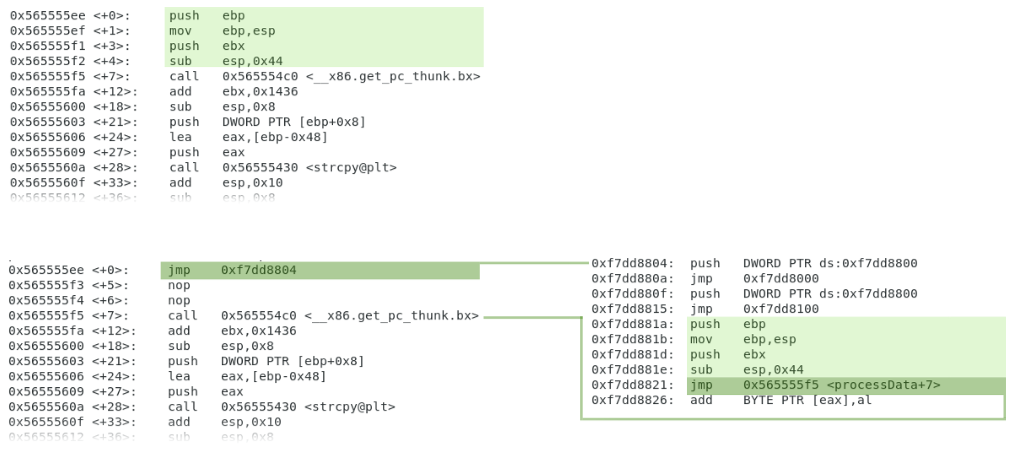

This magic is possible thanks to a mechanism called “trampoline”. Explained in a few words, it simply consists in replacing the first instructions of the target function by others to jump into a controlled area where to jump to specific areas of injected code and, at the end, place the removed instructions and jump back to the function code:

Now we are ready to go for the interesting part! :)

Shielding the return address

Let us get back to the moment when the first instruction of the function strcpy is going to be executed.

At this point, the address to return from strcpy to processData (0x5655560f) is on the top of the stack.

A few positions further down, there is the address to return from processData to main (0x565556a9).

Note that no instruction from strcpy has been executed yet; thus, the register EBP is still pointing to the

base of the stack frame for processData, this is, right on top of the address to return to main.

We we discussed above about the concept of buffer overflow, we differentiated between two key moments:

(1) the instant before strcpy was executed, and (2) right afterwards.

These two moments are depicted in the following image: at the top, before executing strcpy;

at the bottom, after executing strcpy.

Note that, in the former case, the address to return to main is the legitimate one (0x565556a9); whereas in the latter case,

the address has been altered by the exploit (0xf7f568ab). How could we avoid this? If it were possible for us to , somehow,

do actions at these two precise moments, we could first read the 4 bytes of the return address, stored at 0xffffcd9c,

and read it again in the second moment. If the two read values were different, we would have detected the buffer overflow

and we could abort the execution of the program.

Regarding the address where the address to return to main is stored, this could be obtained from the EBP register, since it points to

the 4 bytes preceding the return address.

So we have two moments where we would like to act… Is that even possible? If we recall what we have seen about Frida and the Interceptor, we will

realize that it is. The Interceptor gives us the opportunity to take action before and after the execution of the “hooked” function,

which can be done by writing out code within the callbacks onEnter and onLeave, respectively.

The snippet below shows a minimalist implementation of the algorithm:

-

In the

onEnterblock, the address where the address to return tomainis located is referred to asthis.callerRetAddrPtr. It is obtained from the registerEBP, as it is placed 4 bytes after. This address was represented as&ain the previous image. Next, if we dereference the pointerthis.callerRetAddrPtr, we obtain the address to return to main, which is stored in the variablethis.originalCallerRetAddr. -

In the

onLeaveblock, the pointerthis.callerRetAddrPtris again dereferenced and the value obtained,callerRetAddrBeforeRet, is compared with the value ofthis.originalCallerRetAddr. If they differ, a buffer overflow has been detected and the execution can be aborted.

Interceptor.attach(Module.getExportByName(null, 'strcpy'), {

onEnter(args) {

this.callerRetAddrPtr = this.context.ebp.add(4);

this.originalCallerRetAddr = Memory.readPointer(this.callerRetAddrPtr);

},

onLeave (retval) {

var callerRetAddrBeforeRet = Memory.readPointer(this.callerRetAddrPtr);

if (this.originalCallerRetAddr.toString() !== callerRetAddrBeforeRet.toString()) {

// abort

}

}

});

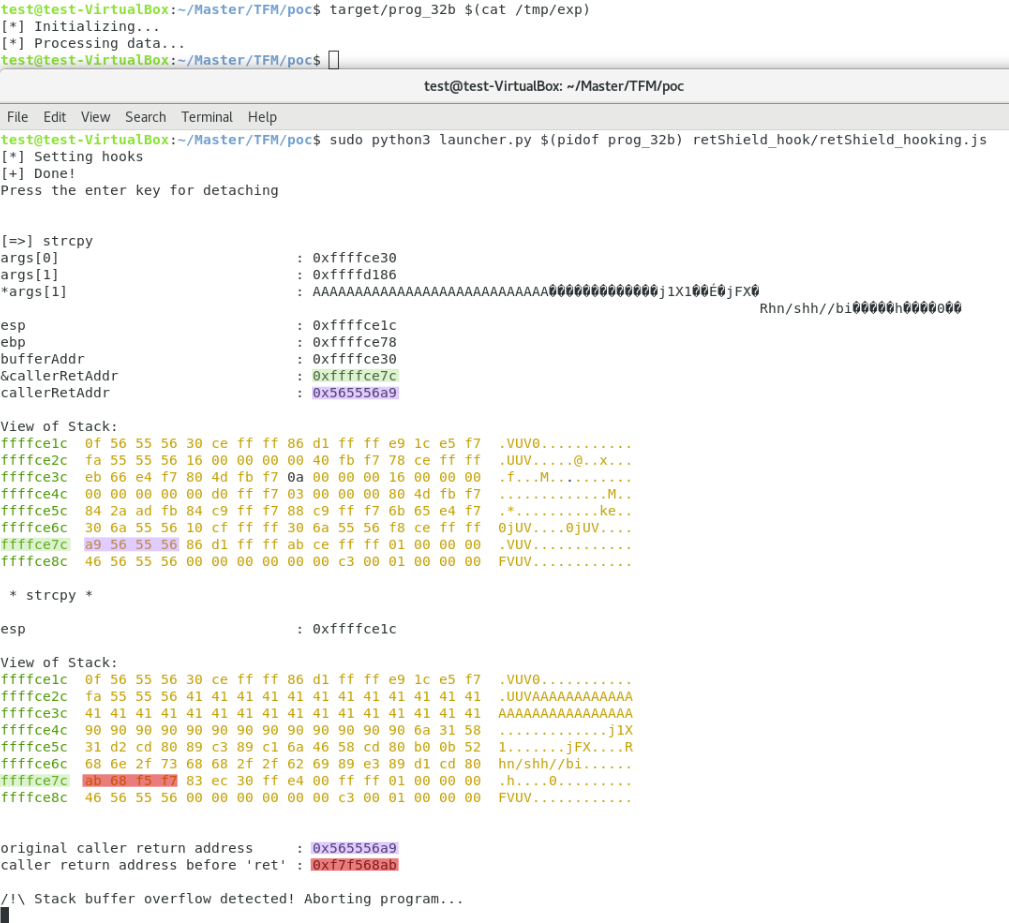

In the picture below, we can observe how the application of this strategy results in the neutralization of the exploit, which does not return a shell.

What else?

If you feel like playing with this PoC, you can check out the git repository retShield.